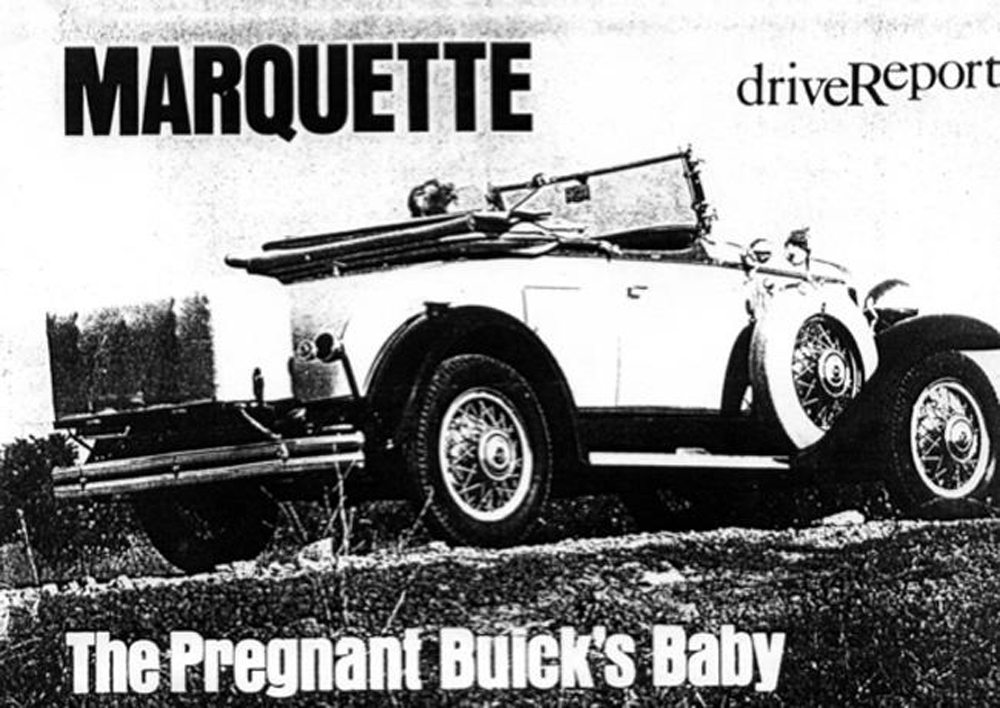

THE BIG Joke of 1929 was that year’s new Pregnant Buick. People thought the car looked pudgy. It did – its body bulged out over its belt line as though it were about six months pregnant. The word “pregnant” was pretty risque back in 1929, so the phrase “Pregnant Buick”, followed by a snigger, swept the country.

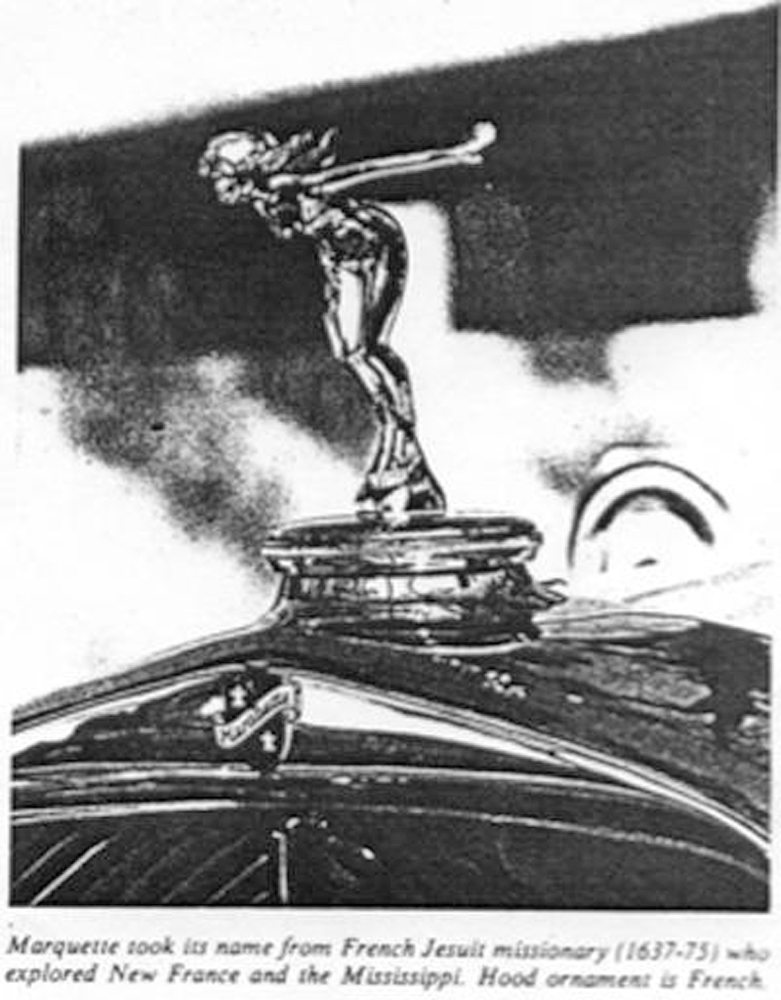

When the Marquette arrived in dealer showrooms on June 1, 1929, America laughed even harder, because here was a Baby Buick – proof of the big Buick’s pregnancy. Thus both parent and child entered the Depression with two strikes against them. GM’s decision to launch a Buick companion car cost the company untold millions of dollars. Buick plowed $26 million into the Marquette initially and then sold a grand total of 27,821 units in the U.S. during 1929 and 1930. That comes to just over $1000 per gross expense, which was about the average retail price of each one sold. In other words, Buick lost all monies spent on materials, labor, tooling, manufacturing, advertising, and other expenses. (Some 7000 additional Marquette’s were sold in Canada, Mexico, and overseas for a production total of 35,007).

The companion-car idea went back to 1924-25 when decisions were made to give Oakland the Pontiac for 1926. Cadillac the La Salle (1927), Olds the Viking (Apr. 1929) and Buick the Marquette (June 1929). These decisions were intended to give GM fuller market coverage, so there would be one car (or several cars) in each price range, from the least to the most expensive, S’s companion-car fever.

The Marquette was developed during 1926-28, partly in Flint under Buick?s chief engineer, Ferdinand A. (Dutch) Bower, but also with big helping hands from GM Research and the Fisher Body Co. The decision to go to an L-head 6 came straight from the 14th floor of the GM Building and certainly not from Buick. Some of the engineers who helped create the Marquette affectionately dubbed it the “Oldsmobuick”, because its engine was essentially a reworked Oldsmobile F-28 – the L-head 6 that Olds introduced for 1928. This engine turned out to be a very good one for Oldsmobile: highly successful. It served Olds from 1928 through 1936 with only minor modifications. It sold extremely well and gave good value. Buick took the 1928 Olds 6, increased displacement by 15.3 cid (bore up 1/16 inch: stroke down half an inch) and then decreased the diameter of all four main bearings. Why shrink the mains? Well, in the interest of manufacturing economy. But the Marquette got away this cost cutting. After Buick stopped building Marquettes, all tools and dies to produce this 6-cylinder engine were shipped to Adam Opel AG in Germany and the Marquette L-head 6 became the 3.5 litre Opel-Blitz light truck engine and found some use in the military.

Buick sales had been slipping since 1926. The division registered a record high of 266,753 that year. But by 1930, production had dropped to 119,265, and Buick was in serious financial trouble (along with everybody else, of course). In 1929, which was a bountiful year right up to the Crash, Buick barely managed to find registrants for 156,817 cars, some 40,000 fewer than it built. Part of this downturn came via the Pregnant Buick. Part came, too, from the fact that you could buy an OHV 6 from Chevrolet in 1929 for about half the cost of a Buick. Buick dealers were fast taking on franchises for other makes of cars, mostly less expensive lines like Chevy, and those who still had exclusive Buick dealerships were screaming for Flint to bring out something cheaper, something that cost less than $1000.

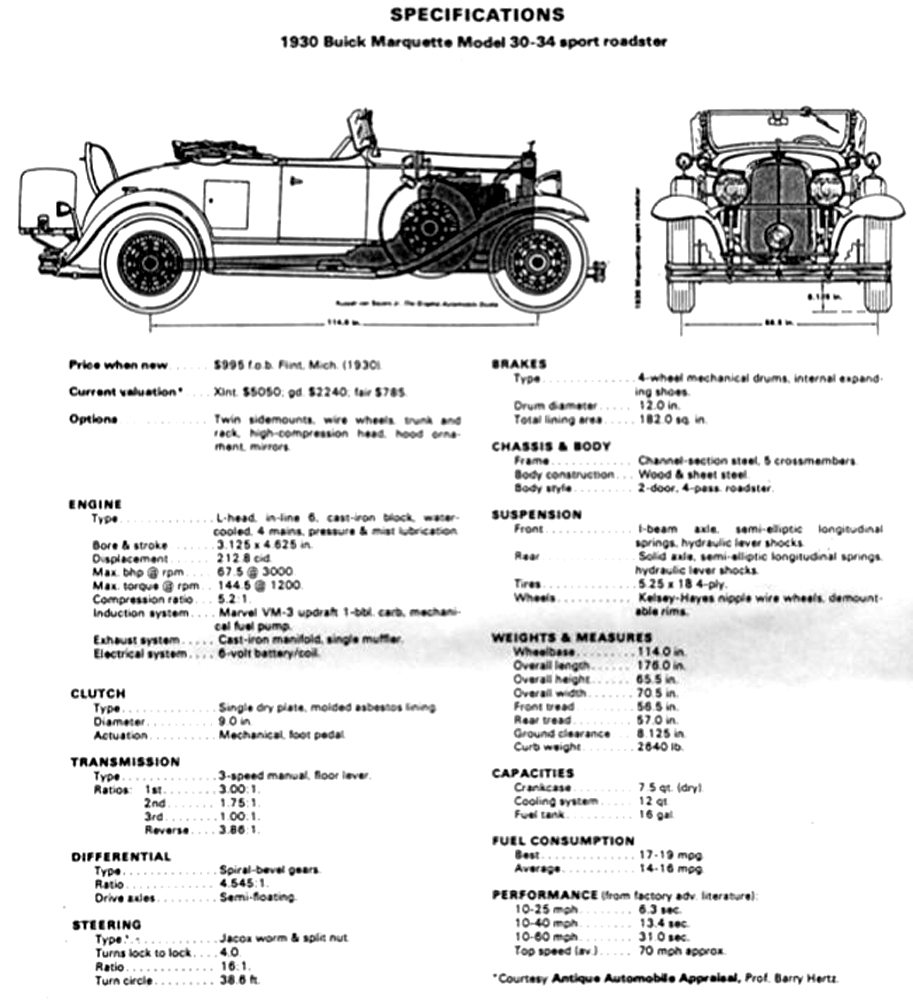

Enter the Marquette. Pre-production publicity and teaser advertising popped up in Apr. 1929. Overnight, mention of the Marquette blossomed everywhere, stirring enthusiasm among dealers and customers alike. Here was a brand-new car, a high-performance car, from the great and reputable manufacturers of Buick, and for less than $1000. An early ad ran, “The Most Complete Car in America Priced Under $1,000. What a startling statement that is, yet how convincingly the new Marquette fulfills its ever word. Underneath the hood is a six-cylinder engine which accelerates from 10 to 60 miles an hour in less than 31 seconds: an engine which delivers 68-70 clocked miles per hour: an engine which will climb any 12% grade in high!”

Marquette’s publicity and advertising were very cleverly planned and staged – one of the first integrated campaigns with everything color-coordinated. Ads were all on a deep plum background, with unique type faces, emblems, and (later) line drawings of the cars themselves. These same colors and treatments extended to all brochures, sales literature, dealer banners, and even shop and owner’s manuals. So often when a car promises everything new and there’s nothing actually new about it, that’s part of what holds it back. The Marquette turned out to be conventional in every way: the engine, 3-speed Muncie gearbox, 9-inch dry clutch, 4.54 rear end, suspension, tapering ladder frame, and composite body. It was all very nicely done and well put together, but as a new car, it was almost too much like all the rest. About the only thing different was the induction system. This used a tube-fed hotbox above the updraft Marvel carburettor.

As for styling. AUTOMOBILE TOPICS commented that the Marquette, “…would do very well in looks as a small edition of the Cadillac.” The Marquette looked good, but no better than other cars in its class. Actually it shared some body pressings with Oldsmobile. The Olds F-29’s wheelbase was only half an inch shorter than the Marquette’s (113.5 vs. 114.0). And unfortunately for the Marquette, Oldsmobile prices were exactly the same as the Marquette’s, so Buick was challenging an established, successful nameplate with an unknown newcomer.

As first introduced, buyers got no color options. All 4-doors were blue, all roadsters buff, etc. Later, though, Buick bowed to sales pressures and made different color choices available.

The baby Buick came in six body styles: 2- and 4-door sedans, sport and business coupes, roadster, and touring car. As first offered in June 1929, prices ranged from $965 for the business coupe to $1035 for the 4-door. On dec. 9, Edward T. Strong, Buick’s president, announced a price increase on all Marquettes (and Buick), and the range now extended from $990 to $1060. From June through Dec. 1929, Marquettes found 15,490 buyers, meaning that dealers sold about one Marquette for every 10 Buicks. In 1930, Marquette registrations totalled 12,331. Buick called a halt to Marquette production late that year. A few leftovers were sold in 1931 and registered as 1931.

The Marquette, though, didn’t simply die and disappear. We’ve already mention what became of its engine – that it went to Opel to power light trucks and military vehicles. The Marquette’s body, meanwhile, was given over to the small Buicks of 1930-31. The 1930 Buick 40 roadster used the Marquette’s body with four inches more wheelbase and a longer hood. In 1931, with the first Straight 8’s, the Buick 50 series used bodies practically identical to the Marquette’s and even reverted to the 114-inch wheelbase, So Marquette helped Buick shed its 1929 maternity wardrobe at a time when Buick needed a new look in a hurry.

The Marquette surely deserved to survive as much as any established car of its day. Why didn’t it? For a number of reasons. First and foremost, the Depression – not many people were buying cars of any sort after Oct. 1929. Second, buyers had their choice of too many good $1000 6’s at the time: Auburn, Chandler, the Chrysler 65, DeSoto, Dodge, Durant 66, Elcar 75, Essex Challenger, Graham-Paige, Nash, Olds F-29, and Pontiac. For $300 more, you could move up into a big Buick. For $300 less you could buy a Chevrolet 6. Third, the Marquette was fighting both sides of the “new” battle. For those who wanted something really new, the Marquette didn’t have it. And for those who tended to be conservative, why try an unproven model when you got pretty much the same thing from any number of more familiar cars? To the conservative buyer (and most were in the early 1930’s), the Marquette simply didn’t look like a sure thing.

Special Interest Autos spent roughly a year tracking down a mint Marquette, and we finally found a lulu in Downey, Calif. The roadster you see here belongs to Blair Davidson, a building construction superintendent for Security Bank in the Los Angeles area. Mr. Davidson bought the car in 1967 in 40-point condition. Mr. D. does all his own restoration work, and he does it to absolute perfection. His Marquette took a first-in-class in the only show it’s ever entered – a regional AACA meet in 1972.

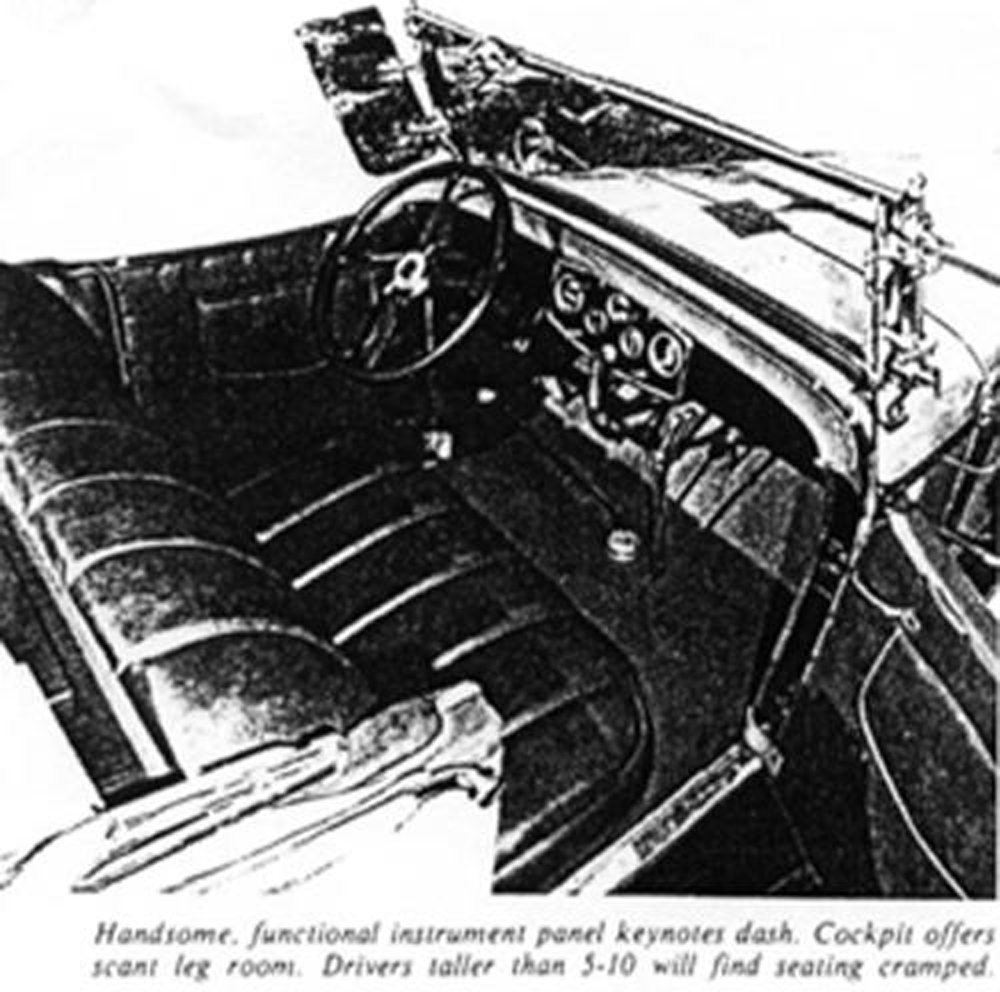

Our drive Report began as we headed south from Downey toward the little town of Brea, some 15 miles away. Brea is one of those rare Southern California holdouts against the big bulldozers. It’s still surrounded by citrus groves – very green and lovely. We began our drive with the roadster’s top up, but the weather was so nice (71° on Jan. 13) that we soon stopped and put it down. The Marquette’s engine, which registered only 155 miles since its restoration overhaul, lights on the first twirl. All it takes is a firm toe on the starter pedal. The clutch depresses easily, and after a second’s hesitation, the non-synchro gearbox slips crunchlessly into low. Low gear, it turns out, is almost unnecessary, because the 4.54 differential allows easy starts in second with just minimal clutch slipping. Shifts between gears also demand a moment’s hesitation to let the cogs mesh.

Up to 30 mph, the Marquette accelerates alongside most modern automobiles. The first two gears moan a lot, but there’s no gear noise in high. After 30 mph in high, though, the Marquette picks up speed relatively slowly, and while we realize that the factory put top speed at 68-70 mph, anything above 50 is strictly pushing it. At 50, the engine?s turning 2800 rpm, and considering that horsepower peaks at 3000, that’s plenty of revs. She’ll wind out to about 3600 if you’re really completely heartless.

Ride feels choppy but not uncomfortable. Our 11-year-old son in the rumbliest found out why they call it that. Sitting over the rear axle, he discovered that only the bend in his knees kept him from flying out when we crossed rain gutters at intersections doing 45 mph. Those same bumps didn’t bother us at all in the front seat. The car seems to corner well, although we didn’t do anything very acrobatic. Steering is pleasantly light and positive at all speeds. Doors are relatively small, as in most roadsters, and you sit very low – practically on the floor. Also, there’s not much leg room. Anyone above about 6-2 absolutely couldn’t stay behind the wheel for more than about 10 miles without hollering uncle. It’s cramped enough if you’re our height – 5-9. But that’s what you expect from a roadster. It’s a very basic car, and that’s as it should be.

The thrill of a roadster at 50 mph is something today’s generation can’t appreciate unless, by some happy fluke, they get to drive a car like this Marquette. It’s great fun, because you become part not only of the car itself but even of the road and the wind. During the six pleasant hours we spent driving and photographing Blair Davidson’s roadster, there must have been 50 people who asked what it was. Marquette? What’s a Marquette? By Buick? You mean the Buick they make now? What has happened to it? How long did they make it? And so on and so forth. As a conversation piece, the Marquette beats the Model SJ Duesenberg hands down.

Posted 08/2004